Currently, I am teaching a course in Advanced Microeconomics where I have started with the premise that conventional economic theory, both Micro and Macro are fundamentally wrong. The number of ways in which they are wrong cannot even be counted. Instead of enumerating errors, the course is devoted to providing a constructive alternative. A lot of the early lectures deal with the basic concepts of optimization and equilibrium, the fundamental building blocks of conventional courses, and explain how these are wrong. I also explain how economists are using a wrong methodology, and how they misunderstand the concept of a theoretical model, and the relations between models and reality. The video-taped lectures, PPT slides, and some supporting materials, are available from my website: https://sites.google.com/site/az4math/

Originally, I had not planned to teach Karl Polanyi because his theories are significantly more complex than those of Karl Marx and Adam Smith. However, because the class has been very receptive, and has understood the what I have been teaching, I have decided to explain his ideas. We have already started discussing his ideas starting from Lecture 13, and have finished Part I of the Great Transformation in Lecture 16. In order to prepare for the complexities of Part II, I have distributed the following handout to the class, to explain the complex general methodological framework which underlies Polanyi’s analysis.

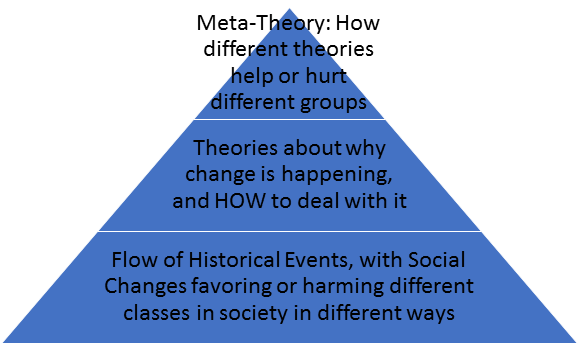

Polanyi operates at a meta-theoretical level. This means that he analyzes theories which emerged as people tried to understand the historical process of social change that was taking place. A diagram may help to make this clearer:

To understand Polanyi, we have to be able to think on three levels at once. At the first level, we have HISTORY, which is just a set of events and observable processes taking place in the real world. Polanyi concentrates on the process of social change. Thinking in terms familiar to economists, Polanyi posits that we start at some equilibrium outcome of previous historical processes, and then we introduce a factor which creates a disturbance in this equilibrium. The process of social change is initiated “as a rule, by external causes, such as a change in climate, in the yield of crops, a new foe, a new weapon used by an old foe, the emergence of new communal ends, or, for that matter, the discovery of new methods of achieving the traditional ends.“

The goal of the book is to analyze this process of social change. In our class, we are not studying European, and in particular, English history, to learn about what happened in England over the past few centuries. We are learning this to understand the process of social change, and especially how this process generates theories about social change. The social change process affects different groups of people in the society in different ways. These groups think about the change which is taking place and try to analyze it. As Polanyi says, in the early stages of social change, people are naturally quite confused about what is happening, and often the theories they come up with, to try to understand the change, are very poor. Nonetheless, it is in the light of these theories that they respond to what happens. It is very difficult to think in terms of abstractions, without having specific concrete illustrations in mind. Therefore we provide an example to illustrate these ideas.

ILLUSTRATION: The process of enclosures dispossessed large number of people from access to land, thereby creating a new class of people unable to survive on their own. This was how “poverty” was created. This requires further clarification — while the poor have always been with us, they have not been a social problem because they have access to land, which can provide subsistence level sustenance. They also have social sympathy, which provides for their urgent needs in emergencies. The market economy destroys both of these support systems, and thereby turns poverty into a social problem.

The creation of the poor, without any means of survival, is what created the labor class, which enabled an early start to the industrial revolution in England. The question of “who are the poor?” was widely debated, with diverse answers being given, in the 18th century. When the French Revolution took place, the question became pressing, since there was fear among the wealthy that mass unrest among the poor might lead to a similar outcome in England. The majority of the theories attributed the emergence of the poor to external causes, and therefore advocated humane measures which would provide them with the help and assistance they needed to survive. In the midst of this debate, the publication of Malthus’ Essay on Population came as a bombshell. According to Malthusian theory, the cause of poverty was over-breeding – the poor population increased geometrically due to high birth rates, outstripping the increases in food supply which increased linearly. Thus, socialistic measures to help feed and shelter them would increase poverty, by increasing the number of the poor. Responses to poverty were then taken along lines in accordance with Malthusian ideas. Support was provided in poor-houses, but the conditions were degrading and humiliating. Segregation by sexes and sterilization were also Malthusian remedies.

In fact, Malthusian theories were wrong, as has been amply established since then. Food supplies over the centuries have increases at a rate slightly faster than the geometric growth of population over the past two centuries. Also, research has shown that poor have children as old-age insurance policies. In environment of high uncertainty and mortality, they have more children. Given social security, the birth rates go down. So Malthus reversed the cause and effect relationship, and supported extreme cruelty to the poor as being a natural part of a system of checks-and-balances on population:

we should facilitate, instead of foolishly and vainly endeavouring to impede, the operations of nature in producing this mortality; and if we dread the too frequent visitation of the horrid form of famine, we should sedulously encourage the other forms of destruction, which we compel nature to use. Instead of recommending cleanliness to the poor, we should encourage contrary habits. In our towns we should make the streets narrower, crowd more people into the houses, and court the return of the plague. In the country, we should build our villages near stagnant pools, and particularly encourage settlements in all marshy and unwholesome situations. But above all, we should reprobate specific remedies for ravaging diseases; and those benevolent, but much mistaken men, who have thought they were doing a service to mankind by projecting schemes for the total extirpation of particular disorders

Even though Malthusian theory was deadly wrong, it was widely adopted and continues to command popularity. Now the meta-theoretical question arises: WHY? Even at that time, and more so now, there is a wide variety of alternatives theories available. Among these choices, why was Malthusian theory selected as the basis on which a response to poverty was crafted at the beginning of the nineteenth century in England? The answer has to do with how Malthusian theories suited the interests of the rich and powerful. The theory appeased their consciences by taking away their responsibility, and the policy interventions it suggested interfered only minimally with their profits. Alternative theories would have increased their responsibility and required more expensive interventions. Because of the ability of the rich and wealthy to control the narrative, they were able to ensure that this theory became widely accepted, even though there was no empirical evidence for it.

CONCLUSIONS: Many of the ideas of Polanyi about the process of social change can be explained with reference to this episode. Some of the important lessons are as follows:

- Understanding a sequence and collection of historical events requires supplying a narrative – a story which connects the facts into a coherent sequence fitted with plausible causal chains.

- Currently dominant Western theories of knowledge (JTB: Justified True Belief) divide ideas into the binary of True/False. These theories of knowledge cannot cope with “pluralism” – a multiplicity of truths. These theories cannot make a distinction between the plain historical facts, and the narrative created to assemble the facts into a coherent story.

- According to the binary theory of knowledge, a narrative is either True, or it is False. If it is true, then it is a FACT, just like the facts of history that it explains. If it is false, then it is completely irrelevant, and cannot help us in understanding anything. Pluralism, the idea that more than one narrative may exist to explain the same set of historical facts, is just nonsense – there only one true narrative, all other narratives are false.

- The problems with currently dominant theories of knowledge, explained in items 2 & 3 above, arise from conflating the bottom and the middle level of the knowledge pyramid pictured in the diagram above. Theories about history are mixed up with history itself.

- To understand the world we live in, and the historical processes which got us here, we must start by rejecting the JTB theory of Knowledge – it sets a bar for knowledge which is too high. For most of the ideas that we study about the world we live in, we will never be able to ascertain for sure whether they are true or false. We must live with uncertainties, and we can only judge relative plausibility and levels of compatibility with observations of different theories.

- Given any collection of facts, there always exist multiple narratives which join together these facts into a coherent and causally ordered sequence. For starters, the narratives look different from the perspectives of different social groups. For example, in 1857, there was a mutiny against English rule in India, according to British historians. From the Indian point of view, it could be described as a revolutionary War of Independence. From the Chinese point of view, it could be seen as a battle between the British and the Indians. All three points of view are legitimate from their own perspectives.

- We must give up the search for the Holy Grail; the one true narrative is only available to God. For human beings, we only have different perspectives. By looking at multiple narratives, we see the same set of events from different angles and acquire a richer, three-dimensional understanding of history. It is only after accepting pluralism, a multiplicity of narratives from different perspectives, of varying degrees of plausibility, that the possibility of the third level of knowledge in the pyramid picture above, can be contemplated.

- The most important difference between Post-Modern thought and Modern Thought is this idea of multiple narratives. Moderns believe in the true/false binary and the existence of a unique true narrative, and hence reject pluralism. For the Moderns, only the bottom level of the knowledge pyramid exists. Some Post-Moderns go to the opposite extreme of saying that there is no way to judge between competing narratives, no objective standards of true and false, and hence all narratives are equally true (or false). This involves accepting the second level of the knowledge pyramid, the multiplicity of narrative, but rejecting the third level, the possibility of evaluating narratives.

- Polanyi operates at the third, meta-theoretical level. This means that we look at competing narratives and evaluate them. Evaluation is not only with respect to the true/false binary. Rather we look at how different narratives support or conflict with interests of different social classes. Economists work with the primitive modernist JTB theory of knowledge, and have completely failed to understand Polanyi, who is working with a far more sophisticated theory of knowledge.

- Narratives which support the interests of the powerful generally come to dominate, and become widely accepted. This idea is reflected in the power/knowledge thesis of Foucault. To illustrate, Malthusian theories about poverty became dominant because they favored the classes in power. This is a meta-narrative – that is, it is a theory about which among a collection of narratives will be chosen as a basis for policies and action.

- This resembles the ideas of Marx, who describes history as a class struggle. Each class has their own theories, and the theories of the powerful classes dominate. However, there is a subtle but important aspect of class struggle which dictates the shape of the dominant narratives. This point is emphasized by Marx, and re-iterated by Polanyi: generally speaking, no single class has enough power to unilaterally impose its own theories on the others. This means that the narrative chosen to support the interests of the ruling class must have an appearance of inclusiveness, so as to appeal to other classes as well.

- Numerous illustrations of this can be given. Policies against the poor, like denying them unemployment benefits, are labeled “tough-love” and sold as being helpful to the poor in the long run. The invasion of Iraq was justified by a campaign proclaiming that it was in the interest of global peace, and to free the people of Iraq. Friedman’s theories, which radically favor the wealthy, and encourage ruthless pursuit of profits by corporations without a social conscience, are sold as “freedom for EVERYONE” and morally responsible behavior by corporations. The GNP per capita narrative of economic growth conceals the pro-rich bias of growth by distributing the wealth equally to everyone before measuring the fruits of the growth. Narratives which support power must be carefully constructed to give the appearance of inclusiveness. Karl Marx said that capitalism not only exploits laborers, but requires the laborers to come to believe in the necessity of their own enslavement.

- An important point on which Polanyi disagrees with Marx is class-struggle. Polanyi agrees with Marx that class struggle is the main driver of history within the framework of a fixed social structure. However, a long-term process of social change can create and destroy classes. The peasants as a class were destroyed by the industrial revolution, and a new labor class emerged in their place, with different interests. So one must move beyond class struggle to understand long term processes of social change. Note that, in accordance with point 12 before, in order to create consensus on the economic agenda of the powerful in modern society, neoclassical economic theories must hide the existence of classes and class struggle. This is why it is essential to prevent people from thinking about income distribution; according to Chicago School Nobel Laureate Robert Lucas: “Of the tendencies that are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and in my opinion the most poisonous, is to focus on questions of distribution.”

- Another important way in which Polanyi goes beyond Marx is in demonstrating the interaction of human theories about history with history itself — what I have called Entanglement elsewhere. Since theories about social change shape human responses to the change process, our (often false) theories directly impact on and shape history. This is in conflict with the “material determinism” of Marxist theory. However, it is in line with the famous Keynes quote that ideas of defunct economists rule the world, even though practical people do not realize it , This entanglement also explains the necessity of studying dominant contemporary theories about social change in order to understand history itself.

The enthusiastic response and reception to the radical ideas that I have been teaching has encouraged me to go further and deeper than I had intended to initially. This essay attempts to clarify one of the major hurdles to understanding Polanyi – the need to understand three layers of thinking in order to arrive at the meta-theoretical perspective of Polanyi. In the lectures, we will illustrate this perspective in many different historical contexts. It will be helpful to have this framework in mind, to understand the common method of analyses being applied to a diverse set of situations.

For a brief summary of certain key components of the methodology of Polanyi, as well as links to an extended paper and a video lecture. see: The Methodology of Polanyi’s Great Transformation

I am so pleased that your explanation about how poverty started is correct and according to the theory of Henry George. George also provided a good explanation of the way that poverty can be ended. I suggest you should include this in the course being given too. So many people would benefit were our social system to be more just by using these means!

thats an excellent quote in last line by r lucas.(i agree with most of essay too tho i just skimmed it.) i like r lucas’ theory in a way–as a thought experiment. but i consider him ‘poisonous’ (both of my parents and my sister went to u chicago. one person in my family taught music theory up there. i didn’t want to go there. my dad had classes with m friedman and was totally unimpressed and didnt like him)

What a great post! Thank you, Asad. There are so many angles here I have trouble deciding where to start this comment, so I guess I’ll employ some linearity and take it from the top.

At the top of that useful pyramid: “How different theories help or hurt different groups.” In the 70s a planning technique was used to evaluate the proposed expansion of the London airport, an analysis that showed who wins and who loses. I proposed a similar idea to a politician I worked for. His response: “We elected officials don’t want to know that information; it is too threatening.” I’ve found this to be true ever since. It’s still a good idea to know who pays and who benefits, but perhaps we must not be surprised if our leaders react adversely, because the next question is: “who are your donors?” and many politicians treat that as priveleged secret information.

I’ve found from experience that political leaders also fear discussion that is contrary to Justified True Belief (and what a great label; I avert acronyms, so I won’t call it “JTB”). And so schools in the US teach only one historical narrative, the one that is rooted in the “City on a Hill” civic religion. Thus the emergence of an excellent book, James Loewen’s “Lies My Teacher Told Me”.

I love the approach to discussing poverty and social class. And the plural narratives discussion reminds me of Kurosawa’s great play, “Rashomon”. I detest the binary theory of knowledge and its practice in my country. This mentality also enables binary thinking in politics in the US. Thus I daily confront, “well I voted for Trump because I detest Clinton. What else was I to do?” Hell’s bells, step out of your cultural trance and use your brain!

Your 13 “Conclusions” are so relevant today and clearly expressed. You must receive many positive responses from your students.

I apply all of your conclusions to my own critique of the century-and-a-half-old Neoclassical economic ideology, which I feel we must completely dismantle and replace. (It’s not all bad, there are some bits and pieces to salvage, I’m sure. But the bulk and thrust, toss it!

You are particularly erudite and clear about the whole matter of socioeconomic classes, which George Bush, Senior declared, “we don’t have these in America”.

Superb, Asad.

One of my early teachers (economics) was J. Emmet Mulvaney, Polanyi’s research assistant as noted in The Great Transformation. Both Emmet and I found it very disturbing that Polanyi, when he was taught, was taught to anthropology students; never in economics classes.

Nobody with any knowledge of Karl Polanyi’s thought could ever believe that micro or macro had any foundations in human behavior or that of societies.

I am very pleased to see a competent economist taking his thought as seriously as it warrants.