By John Haly and Dr. Martha Knox-Haly, originally published at Auswakeup Media.

Any monetary sovereign government can address unemployment through social and political means, giving the working class a functional financial safety net. What stands in the way, however, is the political establishment’s lack of will and refusal to renounce neo-liberal ideology, which uses the unemployed as a bargaining chip for the capitalist class. In this two-part analysis, the requirements for genuine full employment are reviewed.

The concerns about getting a job, keeping or leaving a job, and the anxiety of finding another generate concerns in the working class. This is not merely because of the issue of mismatches between skills and job vacancies. Skills mismatch or underutilization (e.g., an engineering graduate working as a waiter) is not as well measured in the USA, as it is in Canada, Australia, and the EU (Sullivan, 2014; Ch 4 Pg 49-51). Lack of access to employment is an additional problem because, as basic statistics consistently show, there are more unemployed people than vacancies. Federal job guarantees are proposed by economists who hope in vain that the political class will minimally support full employment policies. The political class seldom do and haven’t in Australia in over half a decade.

There are numerous solutions to achieve full employment, but confusion about how to define “full”. Although Australia had 3.7% unemployment late in 2023, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) claims we have gone beyond “full” employment (Grudnoff, 2023). Neo-classical economists define “full” as the moment before a “NAIRU” inflation point (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2023). Some economic disciplines have long criticised the NAIRU’s description (Sawyer, 1997). Other post-Keynesian economists have proposed that to bridge the gap between a “NAIRU” version of “full employment” and real full employment. We should look to a Federal Job Guarantee to address any inflation risks that arise when labour is fully consumed (Mitchell, 2020). This employs the “non-accelerating inflation buffer employment ratio” – NAIBER (Madi, 2019). This is a systemic idea for an internal inflation control mechanism conceived of by economists Warren Mosler and Bill Mitchell, amongst others (Mosler, 1997) (Mitchell, 2016).

The counterfeit NAIRU

To address this issue, some points need to be made about the NAIRU. The RBA’s conception of the NAIRU, which proposes a trade-off between inflation and unemployment is one representation (Hutchens, 2023). This will be referred to as the “counterfeit NAIRU”. It presumes that monetary policy can by itself alleviate cost-push inflation (which current global inflation most certainly is). Under its own precepts, monetary policy is only presumed capable of dealing with demand-pull inflation (Grothe, Weber, & Nikiforos, 2024). My second representation is a “legitimate/efficient NAIRU” (to the extent that NAIRU is legitimate) this is refferred to as a “Mismatched Unemployment Inflationary Rate” (MUIR). The phrase “legitimate NAIRU” is applied with caution about labour mismatch-induced inflation, when labour is the economy’s limiting factor of production. MUIR is the point at which mismatches between skills and job vacancies would generate inflationary effects in the absence of a federal job guarantee (Mitchell, 2021). The difference between these approaches is that the NAIRU uses unemployed humans as a buffer stock, whereas a job guarantee uses employed humans as a buffer stock (Sanderson, 2019). The MUIR is the point at which other barriers to unemployment are eliminated. No Western government has made any serious effort to achieve this. All Western governments use the unemployed as a buffer stock (Smith, 2017).

Job Guarantee

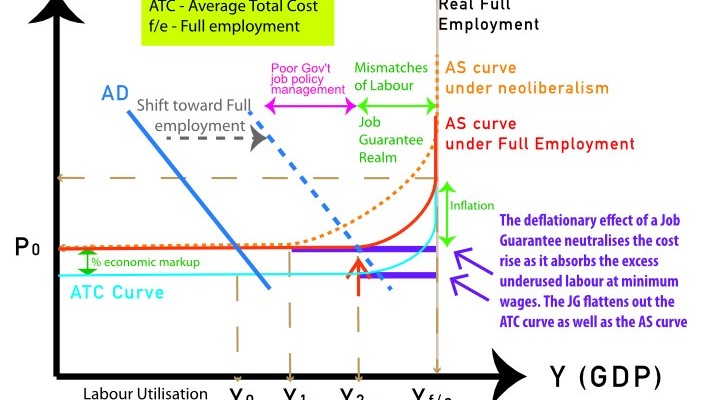

“The general idea of a Job Guarantee (JG) is that the government offers employment to everybody ready, willing, and able to work for a living wage in the last instance as an Employer of Last Resort” (Tcherneva, 2018a). Prof. Bill Mitchell, Pavlina Tcherneva, and other heterodox economists have elaborated on that idea in order to close the inflation risk gap between not-quite-full employment and full employment (Tcherneva, 2020. Pg 116-118). This would leave frictional unemployment as the sole economic concern (Kagan, 2022). With no job guarantee, the path to full employment is susceptible to inflation after the MUIR point. However, as ecological economist Prof’ Phillip Lawn has demonstrated, it looks nothing like a Phillip’s Curve model. (See Figure 1)

Regardless of whether the Reserve Bank of Australia (or the Fed in the United States) believes an economy has passed a legitimate “NAIRU” inflation point (MUIR), very few economies, if any, actually have. Claiming that unemployment should be 4.5% when there was no rampant inflation at 2% unemployment ignores 25 years of history (Karp, 2023). Beyond real unemployment not being as low as claimed, current post-pandemic inflation was initially driven by supply-shocks and then by corporate price-gouging decisions, rather than any evident demand or low unemployment (Haly, 2022); (Haly, 2023).

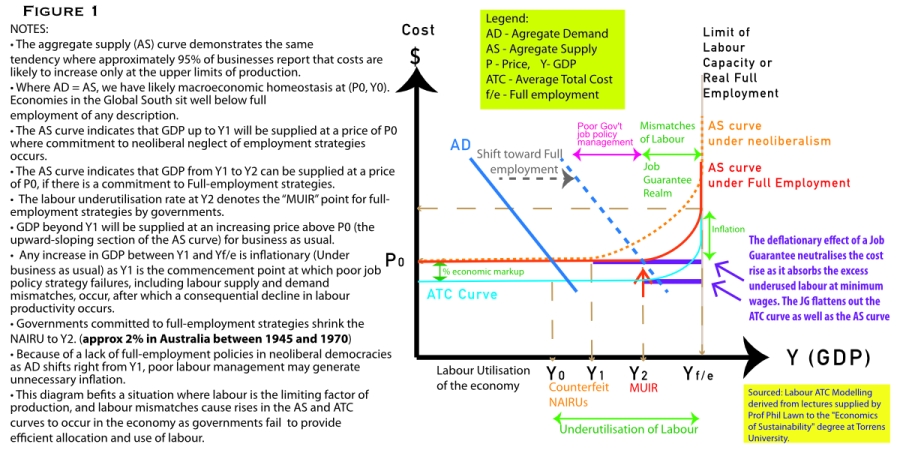

When labour is the limiting factor of production, inflation follows. Labour mismatches induce inefficiency. It affects economic productivity when an economy is near full employment, since, contrary to conventional economic beliefs, labour skills are not interchangeable. The only way they are interchangeable is if they are identical positions. Capacity, experience, and abilities matter. Accountants, labourers, or nurses cannot, for example, fill a deficit of electrical engineers. Mismatches increase when labour skill and experience deficiencies restrict productivity. People may be unable to fill employment openings, resulting in idle or unproductive labour, and therefore increasing the cost of production. This partly explains why job openings in a poorly constituted labour market (without full employment policies) go unfilled month after month, even while unemployment numbers are more significant (Haly, 2024b). (see Figure 2)

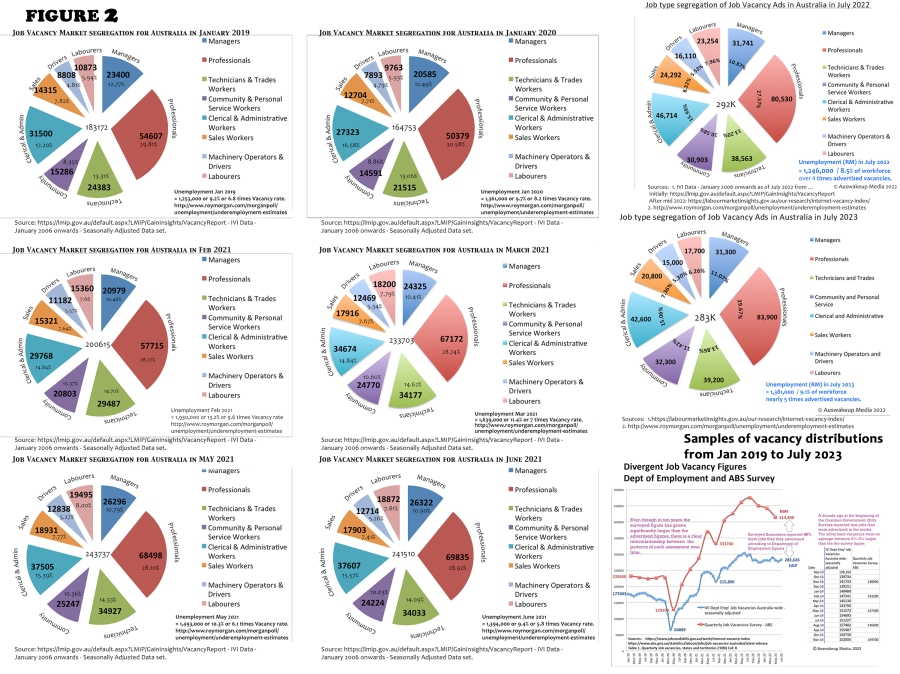

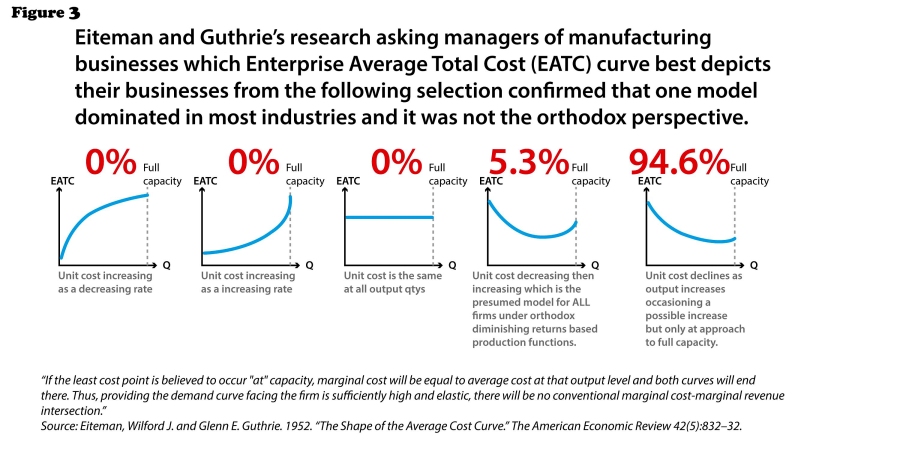

Labour costs become problematic when a mismatch occurs (not to be confused with the government’s failure to implement full employment policies). As labour becomes scarcer, efforts to produce unmatchable substitutes may cause cost-push inflation. Mismatches between labour supply and demand appear at the MUIR point (“legitimate NAIRU”). When mechanical engineers are scarce, you may employ an electrical engineer at either a higher mechanical engineering fee or as an inefficient factor of production. As full employment approaches, labour productivity declines, and expenses increase. This causes businesses costs to rise. According to business surveys, rising costs are more likely to occur near production limits. (See Figure. 3) As a firm approaches that labour limit, your average total expenses grow since each extra hour of labour is less productive. (Figure. 1) Consequently, to maintain profit margins, businesses raise prices, as they are never ones to miss an opportunity to price gouge (Prof. William Mitchell, 2024). That is from where real inflation originates as a pricing decision!

The MUIR

The MUIR point exists in the gap between employment mismatch and true full employment. However, while it is difficult to measure, if full-employment policies are in place, it should be less than 2% (as it was for 25 years in Australia). Figure 1 shows how it looks regarding its effects on average total costs. It should be noted that this is not the standard Phillips Curve used for counterfeit NAIRU. At this point, the federal Job Guarantee for a minimum wage should be used to consume excess idle labour without “mismatch” inflation. If not at the MUIR point, the government should hire at the award wage. You avoid cost-push inflation by consuming idle labour at the point where the event horizon of the MUIR actually exists and doing so at a minimum wage. This is where a Federal Job Guarantee, as defined above, comes into play to compensate for the inefficient excess cost of idle labour. This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the concept of an Employer-of-Last-Resort (Tcherneva, 2018b).

Current ideas of fighting NAIRU inflation through monetary rather than fiscal policy have raised recessionary concerns (Emerson, 2023). Few countries, other than Australia, have implemented full employment policies that have achieved around 2% unemployment (for 25 years with negligible inflation!) through fiscal policies. If these countries were experiencing demand-pull inflation — as opposed to cost-push inflation. It would be due to a failure to implement full employment policies in education, public employment, and mission-based economies (Kibasi, 2021). In Western democracies, full employment policies are not part of the dominant neoliberal agenda. As a result, counterfeit NAIRU employment mismatches happen much sooner than they should. Neoliberalism institutionalises governments’ inability to provide jobs for their citizens.

A change to a fully functionally productive and more egalitarian society, where everyone who wants a job may have one and worker exploitation is reduced, will require the facilitation of both full employment policies and a job guarantee. In the second section, we will examine the policy needs that are required to make this happen, together with the expectations for future labour markets that will remain unfilled in the event that these aims are not met.