{bit.ly/AZgfc} This is a review and a summary of some of the key arguments presented by Mian and Sufi in their recent book “House of Debt.” It highlights the contribution of Mian and Sufi by showing how they have solved the mystery of why there was a huge drop in aggregate demand during the Great Depression of 1929 and also following the recent Global Financial Crisis of 2007-8. The article shows how major economists like Keynes, Friedman, Lucas and others tried and failed to provide an adequate explanation of this mystery. The key to the mystery is the huge amount of levered debt present during both of these economic crises. The solution suggested by Mian and Sufi is to replace interest based debt by equity based contracts in financial markets. This solution resonates strongly with Islamic teachings on finance. The lecture below covers the first three chapters of the book. For the next post in this sequence, which covers chapters 4 & 5, see “Debt, Levered Losses, & Unemployment“.

Atif Mian and Amir Sufi open their book “House of Debt” with a MYSTERY. It describes the human misery caused by loss of 20,000 Jobs in a small town in Indiana. On the macro level, 8 million jobs were lost, and 4 million homes were foreclosed. Hunger & Homelessness in the USA reached the highest levels seen since WW2. Why? There was no apparent cause for this economic disaster; that is, there was no war, revolution, earthquake, tsunami, or pandemic, which would lead to massive loss of capacity for production. The economy was fully capable of producing and providing jobs to all – as evidenced by the fact that it was doing so for decades prior to the Great Recession. So, what happened that made it unable to do so? 33m Video Lecture covers first 3 Chapters of House of Debt, which provide an important part of the solution.

Mian & Sufi start with a quote from Sherlock Holmes: “It is a capital mistake to theorize before you have data”, and proceed to present data. However, the data they present is strongly aligned with the theory they plan to develop. There is so much data that selection of what data to examine must be done on the basis of theories. Our economic theories provide a number of variables of interest, which have been discussed in the literature, and the search for relevant data is always guided by theory. They start data analysis by looking at the dramatic rise in household debt: from $7 Trillion in 2000 to $14 Trillion in 2007:

They note this is similar to GD’29 (Great Depression of 1929): debt tripled from 1920 to 1929. Thus we see that the GFC was preceded by huge rise in debt. The data also shows that GFC started with a huge fall in consumer spending, again matching the pattern of the GD’29.

Of course, this could be just a coincidence, an accidental pattern. Therefore, we examine the International Evidence to see if this pattern is commonly seen globally. We find that Mervyn King, ex-Governor of Bank of England writes in an article entitled “Debt Deflation: Theory and Evidence” that the biggest recessions in the 1990s (those of Sweden & UK) were preceded by biggest increases in debt. Similarly, what Reinhart-Rogoff call the Big Five: Spain in 1977, Norway in 1987, Finland and Sweden in 1991, and Japan in 1992 are all characterized by a similar pattern. The recessions are triggered by collapse in asset prices, leading to banking crisis, and are preceded by large increases in asset prices and debt. This leads to a natural question: are recessions caused by a Banking Crisis or by increasing amounts of Debt? Here an article by Jorda, Schularick, Taylor (When Credit Bites Back) which analyzes 200+ Recessions in 14 countries from 1870 to 2008 provides a clear answer: a close relationship has existed between the build-up of credit during an expansion and the severity of the subsequent recession.

The data show that buildup of private debt goes with severe recessions, but does not establish causality. There are alternative theories which suggest that buildup of debt is a side-show, not a cause of recession. Prominent among these is the Fundamentals View, also known as the Supply Side view. During the Great Depression, economists held that the output or GNP would be created by the factors of production capital and labor. Furthermore, supply creates its own demand, so both factors would be fully employed to create maximal output. Keynesian theory was based on the observation that there was excess capacity – both capital and labor were unemployed – contrary to this theory. For the GFC, we note that there has been no reduction in capital and labor, the factors of production – no war, earthquake, or pandemic, which led to destruction of capital, or reduction of labor force. However, moder supply-siders have introduced Rational Expectations as a fundamental factor. If people had a strong belief in future prosperity, this would lead to taking debt to invest in housing (or stocks). However, changing beliefs could lead to collapse. The recession would be caused by the changes in beliefs about the future. High debt occurs as side-effect of these beliefs but is not a cause. A variant of the fundamentals view is that of Animal Spirits. The difference here is that expectations are not rational. In either case, NOTHING can be done about the recession.

Policy response to the Great Recession which followed the GFC was built around the Banking View, which states that the problem is weakened financial sector. When banks suffer heavy losses, they are unable to supply the credit needs of economy, and this leads to recession. The solution is to strengthen financial sector, by bailing out the banks, and making money available to them at low interest rates. This should get the flow of credit going, preventing the recession. Here the problem is seen not as being too much debt, but the opposite. This corresponds to Milton Friedman’s views that the Great Depression was caused by a contraction in the money supply created when the FED allowed banks to collapse. If we bailout the banks and restore the money supply to normal levels, we would have staved off the Great Depression. According to the banking view, there is no such thing as too much debt. The solution to the GFC lies in creating even more debt.

Three major points-of-view emerged regarding the causes of the Great Depression:

- Friedman: Monetary Contraction created when FED allowed banks to collapse.

- Keynes: Collapse of Aggregate Demand (large reduction in consumer spending)

- Fisher: Debt-Deflation: fall of asset prices leads to increase in real-value of debt. Consumers save to pay debt, and reduce demand for goods. This leads to further fall in asset prices.

To this day, there is no clarity on which is the correct explanation. The responses to the GFC were crafted by Ben Bernanke, chairman of the FED, and a devotee of Milton Friedman. This consisted of bailing out the banks and making massive amounts of money available to them at nearly zero interest rates (an unorthodox policy labeled Quantitative Easing). Atif Mian and Amir Sufi argue that we have massive amounts of data available to us today, and this makes it possible to empirically evaluate the different hypotheses regarding the causes of the Global Financial Crisis.

The Big Picture which emerges from this investigation is that Interest-based Debt is at the heart of the problem. Debt forces the weaker party to bear risk. Negative outcomes can lead to massive losses of wealth to the poor, leading to falls in consumption and consequent recession. The identification of the cause as the nature of the interest-based debt contract leads to a radically different solution. Instead of bailing out bankers, we need to bail out the borrowers. In addition, it is possible to change from interest-based system to Islamic-style musharka contracts, which share risk equitably. Such changes would insulate the system from crises. The GD and GFC are man-made disasters, not inevitable. In particular, both Keynes and Fisher were partially right. Keynes correctly focused on collapse of aggregate demand, while Fisher picked up on the importance of debt (missed by Keynes). Also, Friedman’s theory regarding purely monetary causes, was wrong. We now proceed to do the data-analysis needed to prove these assertions.

We start by noting the harshness and injustice of interest-based debt, as embodied in the home mortgage. A homeowner puts lifesavings of $20,000 as a down payment to purchase home of $100,000. The bank provides him a loan of $80,000 and gets the home as collateral. The mortgage contract guarantees the return to the bank. If housing price declines by 10% to $90,000, then the equity of the homeowner declines to $10,000, wiping out 50% of his net worth. If it declines by 20%, he loses everything. If the house price declines by 30% to $70,000, the homeowner has negative equity. That is, he has to pay off a loan of $80,000 to purchase an asset worth only $70,000. Compare this to the Musharka, an Islamic contract, which makes the bank and the buyer co-owners of the house with equity shares of 80:20. Losses are shared in proportion to the equity share. If the house price declines by 20%, the bank loses 16,000 while the homebuyer loses 4000, in proportion with their equity. Given that borrowers are poorer and lenders are richer, this is a much more just distribution of losses.

We now show empirically how the fall in housing prices wiped out the wealth of the poorest homeowners. The graph below shows the net wealth and debt of households, grouped by quantiles, prior to the GFC:

It is clear from the graph that for the Poorest 20%, Debt >> Assets, while for the richest 20% Assets >> Debt. This just reflects the fact that the rich lend to the poor, which is natural. However, the Interest-based Debt, backed by collateral, insulates the rich from risk! This situation is made worse by High Leverage – that is, a high Debt/Assets ratio. This magnifies the effects of small changes in asset prices on the net wealth of the poor. We will now see how these dynamics played out in the Global Financial Crisis, which was initiated by a huge fall in house prices.

From 2006 to 2009, housing prices fell by 30%. This wiped out lifetime savings of the poorest homeowners. Stock prices fell and then recovered. Bonds which offer fixed returns, had increasing prices over this time period, counter-acting the fall in house prices. Of course, Stocks and Bonds are ONLY held by richer households. As a result, net wealth of the richest households was not affected very much by this collapse of housing. Although the average fall in housing was 30%, there was substantial variation across counties. Some had much larger falls, while others were barely affected. These differentials allow us to assess the relative importance of different causal factors in the GFC.

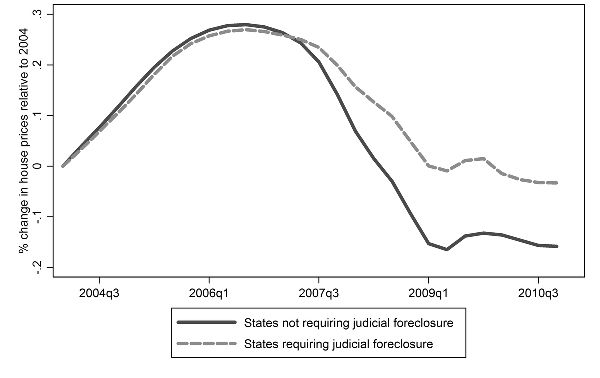

A housing price bubble was created by aggressive lending to high credit-risk households, which were marginal in terms of qualifying for traditional mortgages. This led to higher increases in housing prices in some below median income counties. Correspondingly, there was a larger collapse of housing prices in same counties. On the other hand, some counties were unaffected by these price bubbles. Another factor which caused differentials was foreclosures & fire sales. When homeowners fail to pay mortgages, foreclosure transfers assets from the homeowner to bank. The bank has incentive to sell cheaply and quickly. They have no incentive to maximize profits from the sale, as they only need to recover their equity, and any surplus over this amount would go to the homeowner. Losses are covered by insurance. But these foreclosure sales have strong negative externalities. Housing prices are estimated by sales of comparables in the neighborhood. A fire sale depresses prices for entire housing market in the neighborhood. Evidence for this effect is demonstrated in the following graph by Mian and Sufi:

Some states have laws which require court judgment for foreclosures. This is more time-consuming and expensive relative to other states which do not have such requirements. The graph shows that housing prices declined by significantly smaller amounts in states which required judicial foreclosures. This shows how foreclosures have the effect of depressing housing prices.

The central debate addressed in HoD is the Banking View which dominated policy response to the crisis, versus the Levered Debts view which is developed by Mian and Sufi. Note that the banking view suggests bailing out the banks, while the levered debt view suggests bailing out the indebted households as the solution. According to the Banking View, it was the collapse of Lehmann Brothers in September 2008 – rather, the failure of the government to step in and bailout them out – that led to the GFC. This led to a stoppage in flow of credit. In contrast, the Levered Debt view suggests that decline in housing prices wiped out the wealth of the poorer households, and led to substantial reductions in consumption. This was the source of the Recession which followed.

First, the NBER dates the beginning of the recession in Q4 of 2007, 3 quarters before the Lehmann Brothers collapse. Mian and Sufi argue that residential investment should be considered as consumer spending on housing, and this collapsed well before 2008. “The collapse in residential investment was already in full swing in 2006, a full two years before the collapse of Lehman Brothers. In the second quarter of 2006, residential investment fell by 17 percent on an annualized basis. In every quarter from the second quarter of 2006 through the second quarter of 2009, residential investment declined by at least 12 percent, reaching negative 30 percent in the fourth quarter of 2007 and the first quarter of 2008. The decline in residential investment alone knocked off 1.1 percent to 1.4 percent of GDP growth in the last three quarters of 2006.”

The following graph shows the timing of the decline in various components of spending. These timings tend to support the levered debt view, as we now discuss.

HoD documents declines in consumption spending in different sectors starting from 2007, well before the Lehmann brothers collapse. If the banking view is correct, then stoppage of credit flows to businesses should cause non-residential investment (NRI) to decline. But this started already in Q1,Q2 of 2008, before the Lehmann collapse. It is true that all of the declines – consumption, residential & business investment – became extremely large in Q3 2008, in accordance with the banking view. However, if we look at the pattern of decline in NRI, we see that it follows large decline in consumption. When business saw a steep decline in consumption, they reduced investment, supporting the Levered Debt View. This suggest that it is the consumption collapse which drives the decline in NRI, and not the collapse of credit.

In addition, the geographic patterns (to be discussed) and timings of the decline in consumption and investment are consistent with fall in Aggregate Demand (a la Keynes), and not with fall in banking credit (a la Friedman). While the arguments above are suggestive, they are not conclusive. A Counter-Argument favoring the Banking View can be made as follows. The early decline in consumption and investment occurred due to consumer anticipation of banking crisis. EXPECTATIONS of future collapse played a key role. One weakness of this explanation is that almost no one foresaw the coming crisis (see “Why did no one see it coming?”). A second counter-argument appears even more powerful, and is harder to handle. The system was sputtering prior to Lehmann collapse, but the biggest decline in spending came in Q3 (July, Aug, Sep), the same quarter as the collapse. The counter to this is that the banking crisis did start in Q3 and did have an enormous impact on the economy (just like the dotcom crisis of 1999). However, this impact would have been short-lived, and economy would have quickly returned to normal, if not for the factor of huge consumer debt, which led to the prolonged and severe recession which followed. Establishing this requires arguments not covered in the first three chapters of HoD, which are the topic of this lecture.

Conventional economic theory ascribes no role to debt – one man’s debt is another man’s asset, so the net effect should cancel. This is why Irving Fisher’s Debt-Deflation theory for the Great Depression sank without a trace; see Mervyn King “Debt-Deflation: Theory and Evidence”. An important weakness in Keynesian theory is that it misses the importance of debt. Even though debt was in important part of the mechanism, it is only now being re-discovered by some economists. A standard criticism of HoD arguments is that the decline in consumption would come from a wealth effect alone due to collapse of housing prices. There is no relevance of Debt in this argument. There are two important counters to this argument, both of which show that debt matters a lot. The first is the foreclosure externality already mentioned. This occurs due to debt, and substantially lowers housing prices. The second has to do with the distribution of losses in wealth. If the wealth of the poorer households is wiped out, this causes a substantial reduction in consumption. The same reduction in wealth for the richer households would not have much impact. HoD provides some empirical evidence for the impact of this distributional effect in the following diagram, which depicts expenditure on automobile purchases classified by debt-leverage quintiles of the population:

The Highly Leveraged Households have highest Marginal Propensity to Spend on Autos. This means that a fall in net worth of most indebted homeowners leads to highest fall in consumption.

Chapter 3 of HoD concludes with a summary of the Empirical Evidence we have discussed above. Across the globe in general, and for the GFC in particular, severe and long recessions are preceded by a build-up of debt, and are triggered by a collapse in consumption. Asset Price collapse which triggers banking crises has differential effects on different income groups in the population in presence of interest based debt. Debtors are wiped out, while Creditors are protected. Consumption collapses when net worth of large numbers of people in the lower quintiles falls. Consumption is not affected by much when the net worth of the rich falls. This last statement is illustrated by the DotCom crisis of 2000, which saw a loss in value of stocks of roughly equivalent magnitude to the loss of value in housing prices in the GFC. However, stocks are held mainly by the wealthy, and there was no financial crisis or recession as a result.

Concluding Remarks

What are the lessons that we learn from this discussion of the causes of the GFC, which is based on Chapters 1 to 3 of House of Debt? The first lesson is almost exactly the opposite of the Sherlock Holmes quote used in the opening chapter: “It is a capital mistake to theorize without data (as this creates biases)”. To the contrary, it is impossible to do data analysis without theories to guide us as to which aspects of the data are relevant and important for our analysis. In the modern age, there is too much data to allow us to examine it for patterns without such guidance. Mian and Sufi start by examining the buildup of debt prior to the GFC, but the WDI database lists 1400 data series for 217 economies, and those going for an analysis without a theoretical framework would find many other significant coincidences in the huge data set. As an illustration, no one would think to make a graph of housing price falls in states which require judicial procedures for foreclosures and compare it with states without such requirements, unless we had a theory which tells us that foreclosures lead to negative externalities for housing prices.

These chapters of HoD have been examined in detail because they show how good use of statistics is entangled with theoretical frameworks for understanding the real world. Theories we have about the world guide us to data. In turn, examination of data leads to modifications in theories, which generate new demands for more and different data for evaluation. This in conflict with the idea that we can fruitfully examine data alone, without any knowledge of the real-world mechanisms. We can discover patterns in such analysis, but the meaning and significance of such patterns can only emerge after placing them in their real-world context.

A second important point, which goes against conventional training in statistics, is that data analysis is simple and intuitive. We look at which states had larger falls, who has more debt, etc. Simple comparisons of numbers suffice; no complex theoretical distributions are involved. Conventional analysis substitutes thinking about real world with complex mathematical assumptions about the data, and frequently leads to false conclusions. It is rarely clear to the researchers themselves how much of their results depend on the statistical assumptions they have made, and how little it depends on the data.

The final point is perhaps the most important. Data analysis is always done within a battlefield of interests. The analysis done in House of Debt speaks for the powerless, the 4 million homeowners who got evicted from their homes. Even though the results are intuitively obvious, this analysis did not make it into the hallways of power. Instead, the self-serving banking view was promoted by the powerful financial lobby. This led to policies which bailed out the bankers by giving them subisidies of trillions of dollars for their criminal activities which defrauded millions of poor. Even today, the perspectives presented above are the minority view, and the banking view dominates. The power/knowledge angle is essential to keep in mind in studying statistics.

LINKS to related materials:The next post in this sequence covers Chapters 4 & 5 of House of Debt: Debt, Levered Losses, & Unemployment. See link for a Review/Summary of House of Debt Relevant Chapters from House of Debt.

Bravo! And thanks. It is more than a bit refreshing to find Mian & Sufi contributing to the emergence of compassionate economics (as if people really matter more than playing the ‘WinnersTake All’ pyramid game of the ‘power elite’ & kleptocratic jackals). Now, if we could just get everyone concerned to unite in an alliance for R&D of an integrative metatheory of bio-ethical meta-economics, we might survive plutonomic kleptocracy and enjoy the evolution of bio-ethical post-modern oikonomia (the art of living well).

>

Yes, of course, that implies rehabbing modern ‘economics’ (curing its schizophrenic factionalism) by restoring the principles of Goodness & wellness to the definition of value. Only that will enable an upgrade of the plutonomic piracy paradigm retarding economics, education, etc. Right?